This is a bitesize introduction to Positive Psychology; a model which sets out to

try and answer the following questions:

What leads to some people experiencing positive growth in the face of trauma?

What makes some people more resilient and better able to deal with repeated set-backs?

Are these characteristics able to be defined, measured and cultivated?

This course will take approximately 20 minutes to complete, but this timing will

depend on how fast you read and how much time you spend on the activities.

What is Positive Psychology?

Psychology, in general, sets out to try and nd out more about three areas of our lives:

- To support people experiencing mental distress.

- To make people in general happier or more content.

- To study genius and high talent.

Since World War 2 the eld of psychology has focused heavily on the rst of these, seeking to help those experiencing mental distress. The last two were neglected until more recent years, with the introduction of Positive Psychology as a researchable eld of study.

Now that Positive Psychology has become well established, the research seeks to answer the following questions:

- What leads to some people experiencing positive growth in the face of trauma?

- What makes some people more resilient and better able to deal with repeated set-backs?

- Are these characteristics able to be de measured and cultivated?

Over the last 60 years, substantial research has emerged indicating that Positive Psychology tools and strategies have a signicant benecial impact on personal wellbeing.

These tools and strategies were designed to improve wellbeing for everyone; whether or not they are currently experiencing mental health difficulties. They help to increase the amount of positive experiences we have, assist in developing our self-awareness and provide opportunities to challenge unhelpful habits.

What will this topic look at?

This introduction to Positive Psychology topic will look at the concepts of happiness and wellbeing, subjective wellbeing in relation to research and a few true or false myths. Then we will briey touch on the history of happiness and how our understanding has developed over time with the research.

This will lead on to the development of PERMA; the wellbeing theory developed by Martin Seligman who has brought the spotlight back on what makes people generally happier in life within Positive Psychology research. Then we will look at the six main topics that make up the course as well as the tools and strategies that will be considered in more depth throughout the course. Lastly there is a list of references showing the research behind the course.

Happiness and Subjective Wellbeing

Surveys have asked people what is meant by happiness, and the usual responses fall within three domains: a state of joy or other positive experiences; being satisfied with one’s life; the absence of depression or other negative experiences.

Wellbeing on the other hand tends to evoke a more holistic approach and looks less at positive and negative experiences, incorporating instead other factors including; physical health problems, social relationships, environmental stressors, income etc.

Within the positive psychology literature happiness is often used synonymously with the scientic term ‘Subjective Wellbeing’ . In this sense they are used interchangeably. Subjective Wellbeing, however, refers to people’s evaluation of their lives, how they appraise their lives through their thoughts and feelings.

Discover More:

There are many myths about what will make us happy, the expander below has true or false statements that explore a few of these myths:

History of Happiness

Why study happiness?

Overall society is doing better; the majority of us are able to meet our basic needs, we are living longer and we tend to have better health. As a result people are more and more interested in how to live a satisfying and fulfilling life.

History of happiness

Philosophical and psychological pursuits of happiness began thousands of years ago, across the world. It is Western culture’s commitment to happiness which is fairly modern. Some of the schools of thought behind the study of happiness are listed below:

- Chinese Schools of Philosophy; Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism.

- Ancient Greek Philosophy; Socrates, Epicurus, Aristotle, Plato.

- Islamic Philosophy; Abu Hamid al-Ghazali.

- William James (Psychologist and Philosopher – “the first positive psychologist”).

- Logotherapy; Viktor Frankl – “on meaning”.

- Humanistic Psychology – 1950’s; Maslow.

Historically there were two traditions of happiness; Hedonism and Eudaimonia. Henderson & Knight (2012) review the concepts of Eudaimonia and Hedonism and highlight some of the recent debate about the use of these terms. In spite of the debate it is generally accepted that both describe ways of living and behaving and both are pathways to wellbeing.

Developing PERMA

The Authentic Happiness Theory:

Martin Seligman then went on to create his authentic happiness theory which incorporated the historical hedonic and eudaimonic approaches as well as a third approach; engagement.

The Wellbeing Theory:

In more recent years, Martin Seligman revised his authentic happiness theory into the wellbeing theory and added two more aspects of life to his model.

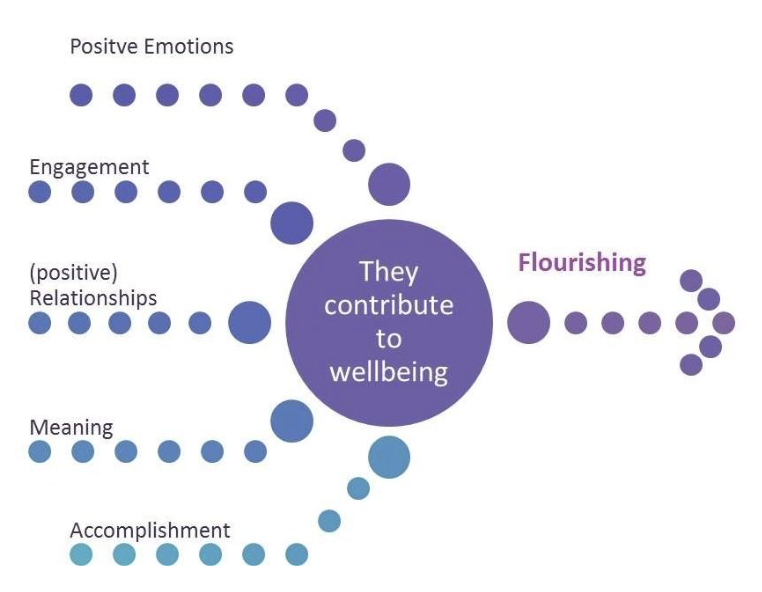

PERMA:

PERMA stands for Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning and Accomplishment. When put together these different lifestyles give us a map to highlight our strengths and give us the opportunity to work on our weaknesses. This theory isn’t trying to suggest that we need to exceed at all of these areas in order to be happy. Simply it is showing that we are individuals and have different needs, wishes and goals for our lives. Also these aspects of life are typically mixed for each of us anyway, you will probably be able to relate to more than one and that’s not a bad thing. Some people are highly driven by one and others are driven by a more diverse range. Seligman suggests that if we get the right balance, for us, between these aspects of life that it will lead to us flourishing.

Course Content

This course looks at six topics within positive psychology as well as tools and strategies that are evidence-based to help us toward improved wellbeing and to flourish in our lives.

The six main topics are:

Strengths

Exploring strengths in everyday actions, the value of knowing your strengths and weaknesses, ways to identify your top strengths and how to build upon them.

Positive experiences

Exploring the meaning of positive experiences, hopes and fears around considering them, why they are important to wellbeing, the advantages of negative experiences of emotion and what brings you positive experiences.

Self-compassion

Exploring the difference between compassion and kindness, barriers to self-compassion, why it is important to wellbeing and how we can foster our own self-compassion.

Mindset

Exploring where our mindset comes from, the difference between a fixed and growth mindset, the helpful and unhelpful aspects of both, how to develop a growth mindset and the benefits of this to our wellbeing.

Positive relationships

Exploring your current positive relationships and what the foundations of these are, considering the way that we interact with others and how to develop active, constructive responding.

Optimism and pessimism

Exploring optimism and pessimism as explanatory styles and how these influence wellbeing, considering the helpful and unhelpful aspects of both and ways to balance our approach to past negative experiences.

The activities within this course are intended to help with self- reflection and personal growth. You will often be asked to consider how you think and feel about the activities and topic content. Not everything in the course is going to be helpful for you, it is individual which tools and strategies will bring the most benefit. It is recommended that you try everything within the course at least once and then continue with the activities that have helped you the most.

Tools and Strategies

Good things in life:

An exercise designed to help us stop and think about the good things that happen to us. Sometimes we can get caught up in the negatives of life and forget to stop and appreciate that lots of things go well too. A good example of this is writing off the whole day because of a bad 30 minutes; we may have had a terrible journey to work, the traffic was bad, the bus was late and we were left standing in the rain. The rest of the day may feel bogged down by this but we can stop and try to think about what went well; the meeting that day was constructive, lunch was enjoyable and a friend called to catch up.

Flow:

This is a state of ‘being at one with’ what we’re doing whether that is reading, doing puzzles, creating art, listening to music, working, walking in nature etc. In this state we lose our sense of self to what we’re doing and typically we are so immersed in it that we lose track of time. Later when we reflect on how we felt during these activities we tend to feel that it was a positive experience and that we enjoyed it even if these emotions weren’t at the forefront at the time.

Savouring or dampening:

Positive experiences can be savoured through a variety of strategies; taking a mental picture, expressing our emotions physically (clapping, jumping for joy etc.), stopping to congratulate ourselves, counting our blessings and sharing the positive experience with others. Dampening is the opposite of this and can be a barrier to savouring, examples of this include; negative mental time travel, suppressing emotions, fault finding and distraction.

Acts of kindness:

We all know that we feel good when we do something nice for someone else whether that be giving a gift, helping someone to pick up things they’ve dropped or being there for a friend who is having a hard time. Incorporating acts of kindness into our lives can bring about positive experiences in this way whilst helping us to create meaning and to develop and maintain positive relationships. This effect is also beneficial for our physical health and research suggests acts of kindness reduce stress levels and help to undo the negative impact of stress on our bodies.

Gratitude:

Stopping to appreciate what we are grateful for in life can be very rewarding and bring about positive experiences. It is good for our relationships as we begin to notice the support that others around us are offering or providing, it can remind us of the times when things went well and times when we anticipate others would be grateful to us. Also it can be as simple as being thankful that the weather is nice that day, that somebody held the door open for us or that we haven’t had to visit the dentist in a while.

Learning a new skill:

When we are faced with a new skill we want or need to learn there are ways of going about it that improve our chances of success. The way that we try to tackle this is often based on how our parents, teachers and peers, during our childhood, interacted with and reacted to us in the face of something we found challenging. If we can identify our patterns in learning a new skill we can try to take a different approach in the future.

Materials and References

Reference List

Argyle, M. (2013). The psychology of happiness. Routledge.

Bryant, F. B. (2003). Savoring Beliefs Inventory (SBI): A scale for measuring beliefs about savouring. Journal of Mental Health, 12, 175–196.

Carver, C., Scheier, M., Miller, C., Fulford, D., 2009. Optimism. In: Snyder, C., Lopez, S. (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 303–311.

DeShea, L. (2003). A scenario-based scale of willingness to forgive. Individual Differences Research, 1(3), 201-217.

Diener, E. & Scollon, C.N. (2014) The What, Why, When, and How of Teaching the Science of Subjective Well-being. Teaching of Psychology, 41(2), 175-183.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Dweck, C. (2012). Mindset: How you can fulfil your potential. Hachette UK.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of personality and social psychology, 84(2), 377.

Forgeard, M.J.C., & Seligman, M.E.P. (2012). Seeing the glass half full: A review of the causes and consequences of optimism.

Pratiq ues P sychologiques , 18(2) , 107-120.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2003). The value of positive emotions. American scientist, 91(4), 330-335.

Froh, J.J (2004). The History of Positive Psychology: Truth be Told. NYS Psychologist.

Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., Impett, E., & Asher, E. R. (2004). What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 228–245.

Gable, S.L & Haidt, J. (2005) What (and Why) is Positive Psychology. Review of General Psychology, Vol. 9, No. 2, 103– 110.

Grant, A. M., & Schwartz, B. (2011). Too much of a good thing the challenge and opportunity of the inverted U. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 61-76.

Harbaugh, C.N & Vasey, M.W (2014) When do people benefit from gratitude practice? The Journal of Positive Psychology Vol. 9 , Iss. 6.

Henderson, L. W., & Knight, T. (2012). Integrating the hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives to more comprehensively understand wellbeing and pathways to wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3).

Huta, V., & Hawley, L. (2010). Psychological strengths and cognitive vulnerabilities: Are they two ends of the same continuum or do they have independent relationships with well- being and ill-being?. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(1), 71-93.

Jose, P. E., Lim, B. T., & Bryant, F. B. (2012). Does savoring increase happiness? A daily diary study. The Journal of Positive

Psychology, 7(3), 176-187.

Langston, C. A. (1994). Capitalizing on and coping with daily-life events: Expressive responses to positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1112–1125.

Layous, K., Nelson, S. K., Kurtz, J. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2016). What triggers prosocial effort? A positive feedback loop between positive activities, kindness, and well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1-14.

Linley, P. (2009). Realise2: technical report. Coventry, UK: CAPP Press.

Linley, P., Joseph, S., Harrington, S.,&Wood, A. (2006). Positive psychology: Past, present, and (possible) future. Journal of Positive Psychology, 1, 3–16.

Lyubomirsky, S. & Layous, K. (2013) How do Simple Positive Actvities increase wellbeing? Current Directions in Psychological Science 22(1), 57-62.

Maisel, N.C., & Gable, S. (2009). For richer…in good times…and in health: Positive processes in relationships. In the Oxford

Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2nd Edition (Shane J. Lopez & C.R. Snyder, Eds.) pp. 455-462. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). Flow theory and research. Handbook of positive psychology, 195-206.

Neff, K. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and identity, 2(2), 85-101.

Neff, K. D. (2009). The role of self-compassion in development: A healthier way to relate to oneself. Human Development, 52, 211–214.

Neff, K., Kirkpatrick, K & Rude, S. (2007) Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 139-154.

Nelson, S. K., Della Porta, M. D., Jacobs Bao, K., Lee, H. C., Choi, I., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2015). ‘It’s up to you’: Experimentally manipulated autonomy support for prosocial behavior improves well-being in two cultures over six weeks. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(5), 463-476.

Norem, J. K. (2001). Defensive pessimism, optimism, and pessimism. Optimism and pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice, 77-100.

Norem, J. K., & Chang, E. C. (2002). The positive psychology of negative thinking. Journal of clinical psychology, 58(9), 993- 1001. 66

Odou, N., & Brinker, J. (2015). Self-compassion, a better alternative to rumination than distraction as a response to negative mood. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(5), 447- 457.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of social and Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603-619.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A classification and handbook. Oxford University Press/Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. (2006). Greater strengths of character and recovery from illness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 17-26.

Peterson, C., Park, N., Pole, N., D’Andrea, W., & Seligman,M. E. P. (2008). Strengths of character and posttraumatic growth.

Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21, 214–217.

Popov, L. K. (2000). The virtues project: Simple ways to create a culture of character: Educator’s guide. Los Angeles: Jalmar Press.

Quinlan, D., Swain, N., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2012). Character strengths interventions: Building on what we know for improved outcomes. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(6), 1145-1163.

Quoidbach, J., Berry, E.V., Hansenne, M., & Mikolajczak, M. (2010). Positive emotion regulation and well-being: Comparing the impact of eight savoring and dampening strategies.

Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 368–373. 65

Rath, T. (2007). StrengthsFinder 2.0. New York, NY: Gallup Press.

Seligman, M. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

Seligman, M.E.P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14.

Seligman, M.E.P., Steen, T.A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60, 410–421. 64

Seligman,M. (2011) Flourish

Sheldon, K. M., & King, L. (2001). Why positive psychology is necessary. American Psychologist, 56, 216–217.

Sheldon, K. M., Boehm, J. K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2012). Variety is the spice of happiness: The hedonic adaptation prevention (HAP) model. In I. Boniwell & S. David (Eds.), Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 901–914). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, T., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 31(5), 431- 451.

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical psychology review, 30(7), 890-905.